Germany’s furry blitzkrieg

From a base in Kassel, Germany– once the home of fairy-tale masters the Brothers Grimm — entire panzer divisions of invading Waschbaren (“wash bears”) have been fanning out across Europe for decades.

From a base in Kassel, Germany– once the home of fairy-tale masters the Brothers Grimm — entire panzer divisions of invading Waschbaren (“wash bears”) have been fanning out across Europe for decades.

Native to North and Central America, the raccoon first sailed east across the Atlantic in the 19th century, when its furs were in high demand by the fashionistas of the day. Periodically, a few captive raccoons did manage to escape (in one incident, for example, an Allied bomb hit a raccoon farm outside Berlin in 1945, liberating dozens of the furry inmates).

These minor jailbreaks aside, it was the Nazis who assured the species’ success in the wild. The subjugation of the European continent got underway in earnest in February, 1934, when Hermann Goering, head of the Third Reich’s Luftwaffe and the Reich Forestry Office, gave Baron Sittich Von Berlerpsch permission to release the animals (to “enrich the Reich’s fauna,” apparently) in the vicinity of Kassel, a city about two hours north of Frankfurt.

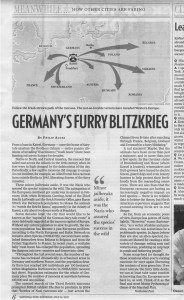

Seven decades later, the city that would like to be known as the “capital of the German fairy-tale route” is more dubiously regarded as the raccoon capital of Europe. Without any natural predators to slow its growth, the raccoon population has become a pan-European problem. According to the North European and Baltic Network on Invasive Alien Species (NOBANIS), raccoons have established themselves from Belarus to Belgium and from the former Yugoslavia to France. In recent years, a veritable baby ‘coon boom has enlarged the population, spreading the diaspora into new countries and deeper into cities.

“Throughout the last several years, the number of raccoons has increased dramatically in urbanized areas in Germany and northern France, and the population density there has reached 100 individuals per 100 hectares,” writes Magdalena Bartoszewicz in NOBANIS’s raccoon fact sheet. Population estimates for the whole of Germany place the number of raccoons at anywhere between 100,000 and one million.

The onward march of the Third Reich’s raccoons prompted British tabloid The Sun to proclaim in 2004 that “hordes of Nazi raccoons are ? just across the Channel from Britain after marching through France, Belgium, Holland and Denmark in a furry blitzkrieg.”

A tad alarmist? Maybe. But the animals have been more than just a nuisance, and in more than just a few spots. In the German states of Brandenburg and Hesse (where Kassel is located), winemakers and fruit-growers have turned to electric fences, guard dogs and even bounty hunters to help protect their livelihoods from the marauding omnivores. There are also fears that the European raccoons are having an increasingly negative impact on bird species — there is no reliable data to bolster the theory, but North American experience suggests that ground-nesting birds are in real danger.

So far, from an economic point of view, Europe has gotten off fairly lightly. “However,” warns Bartoszewicz, “as a vector of rabies and parasites, raccoon can sometimes be a problematic species. In Japan [where they are also an alien species] raccoons are blamed for causing a wide variety of damage: eating corn and watermelons, predating on carp kept in ponds and bothering people.”

Some scrap-food for thought for those occasions when you’re cursing raccoons for once again liberating the contents of your green bin: If we must tolerate the furry little devils, we can at least take some comfort in knowing that the Europeans now have to, as well. Think of it as the final and most Monty Pythonesque clause of the Marshall Plan.

National Post Saturday, July 21, 2007 Page: TO6 Section: Toronto: The City Byline: Philip Alves Column: Meanwhile... Link